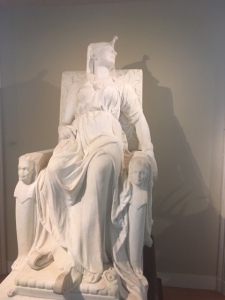

Recently, I visited one of my favorite museums, The National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC. This museum is located right by Chinatown in downtown, a stone’s throw away from Capital One Arena. I was in the area while one of my friends visited from Atlanta, and we took advantage of a sunny afternoon and explored downtown DC on foot. She had never visited this museum before and, since the Portrait Gallery shares a building with the Smithsonian American Art Museum, I thought it would be a great time to visit both. I also got a chance to show her one of my favorite sculptures, The Death of Cleopatra by Edmonia Lewis (I wrote about this breathtaking work in this post).

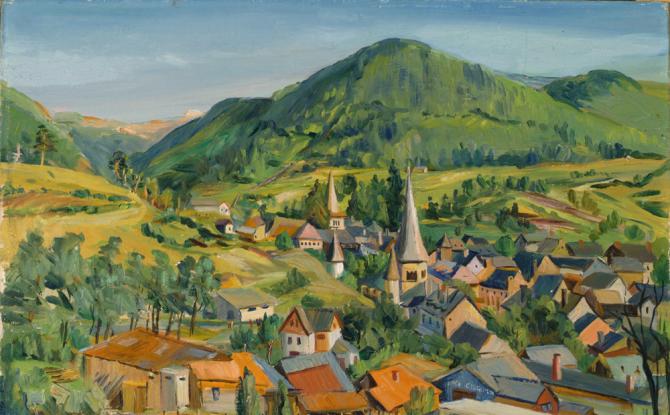

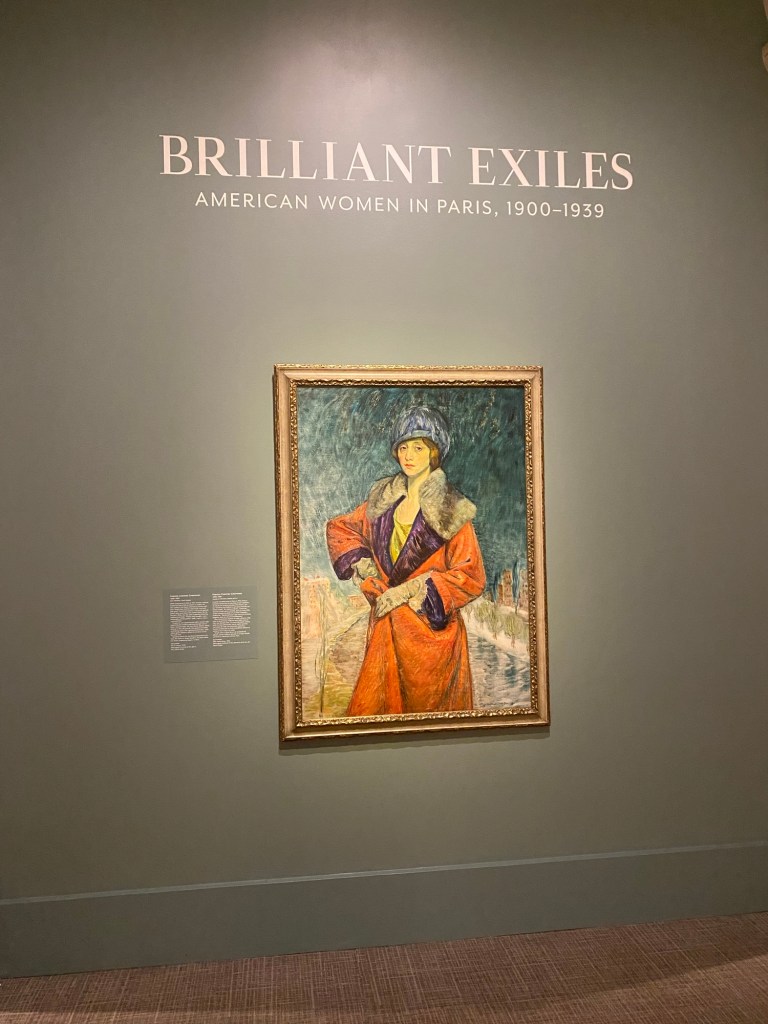

As it just so happens, the museum had two exhibitions that were perfect for our artistic preferences. In this post, I’ll discuss one of those exhibitions (I’ll share the other exhibition in a separate post). Brilliant Exiles: American Women in Paris, 1900–1939 is a stunning collection of works from the various genius women that found themselves living in Paris pre-WWII for the same reason. Paris, during this time, was progressive enough for female creatives who wished to hone their crafts, giving them an environment to do so without the stigmas, pressures, or expectations of life in America. The women were often in Paris for art school, but ending up in some cases staying longer than expected, so they could continue to enjoy the freedom that Parisian life offered.

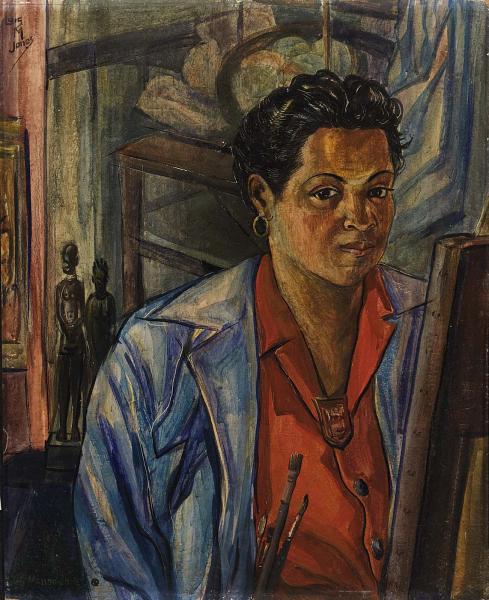

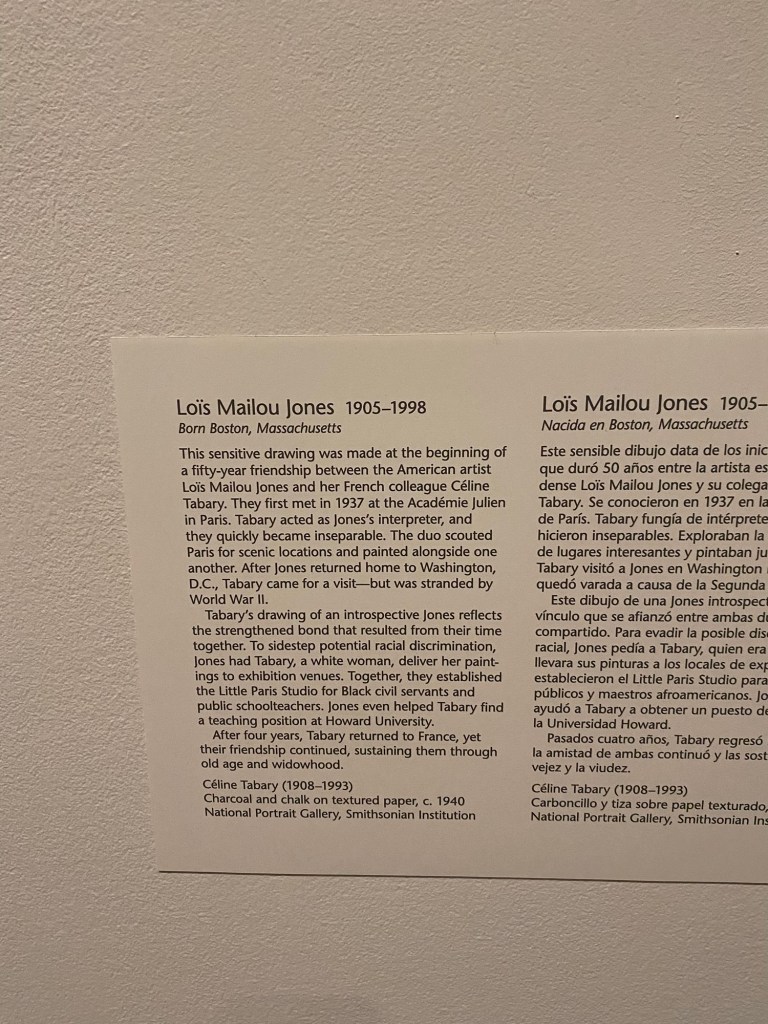

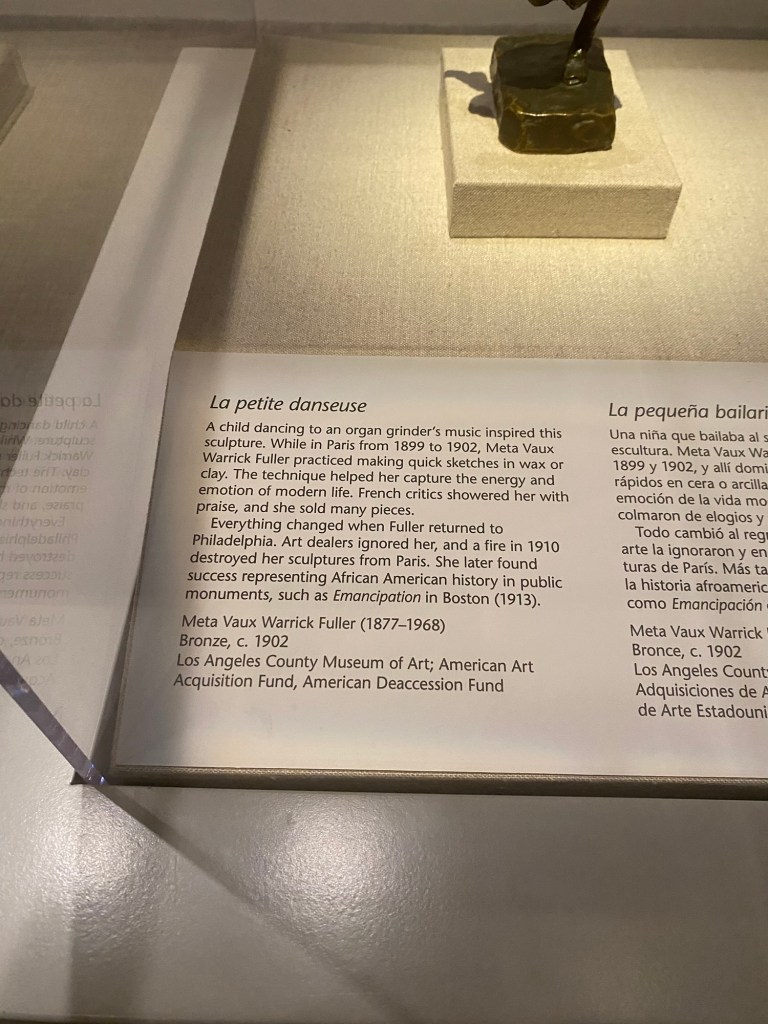

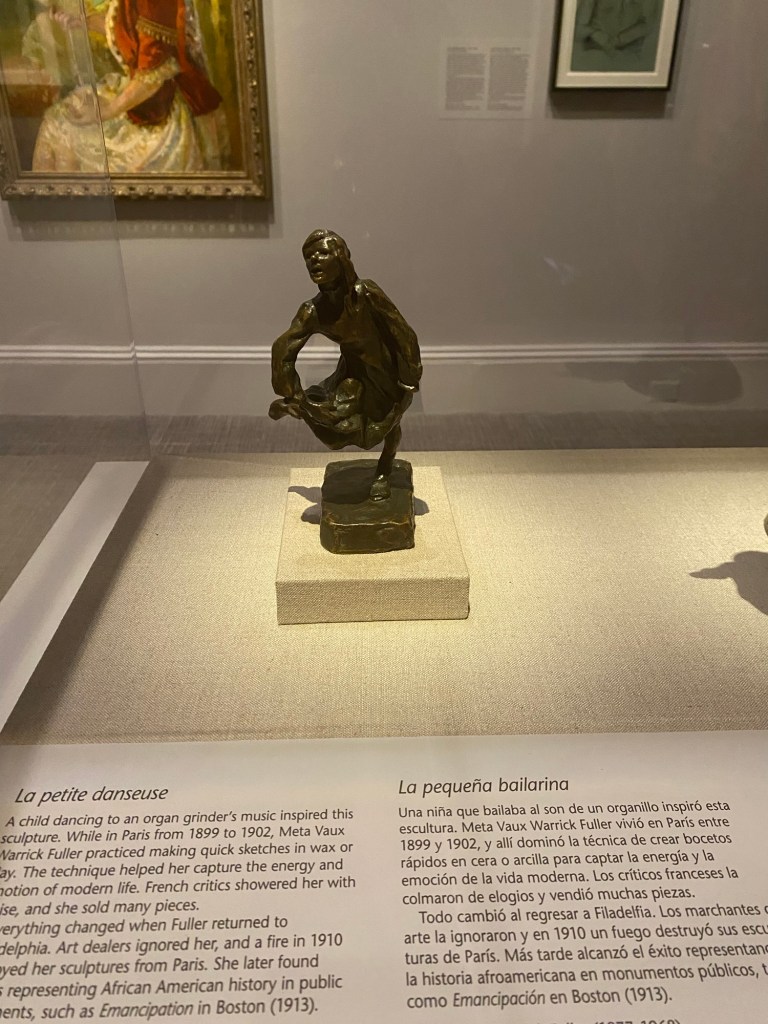

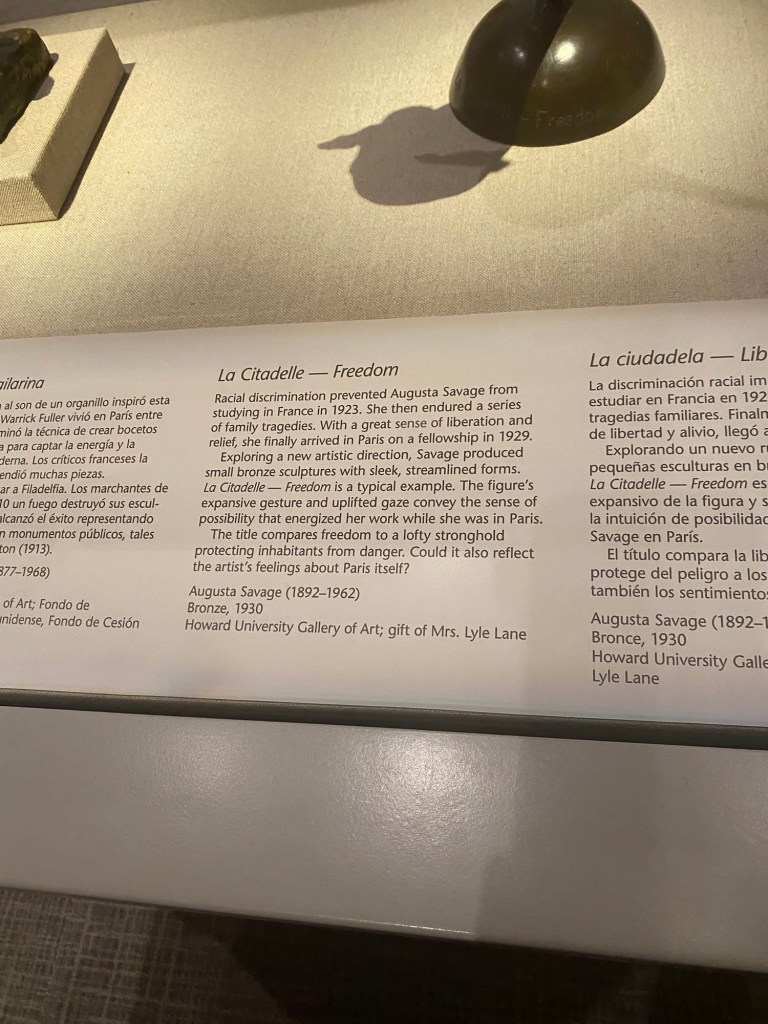

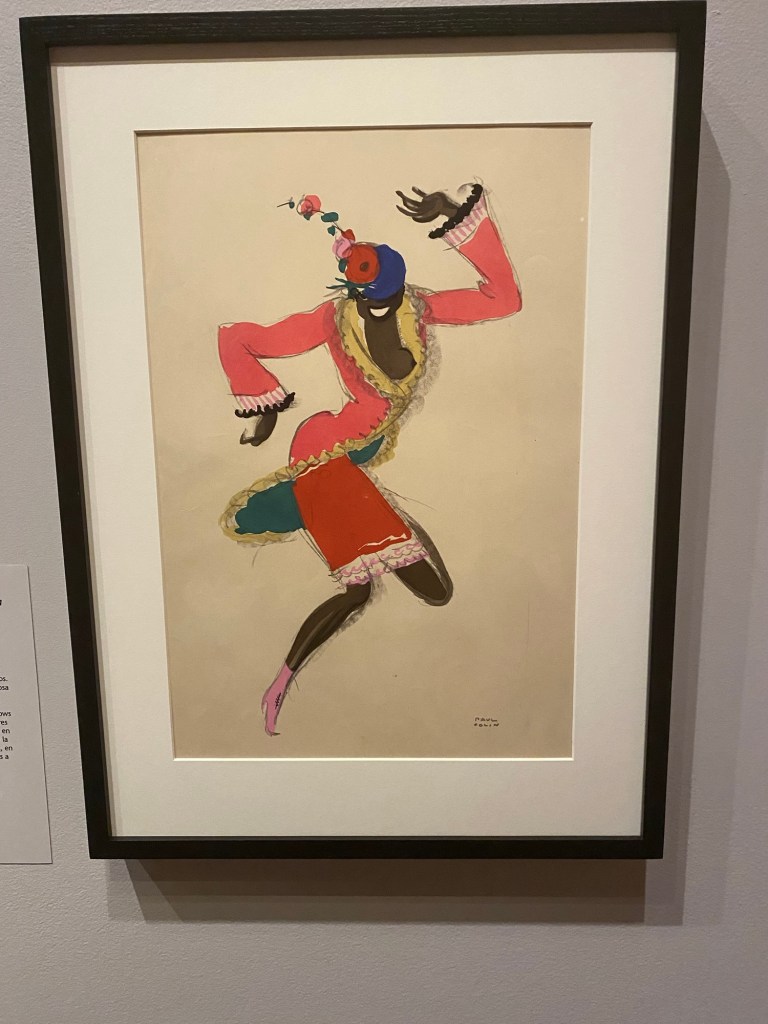

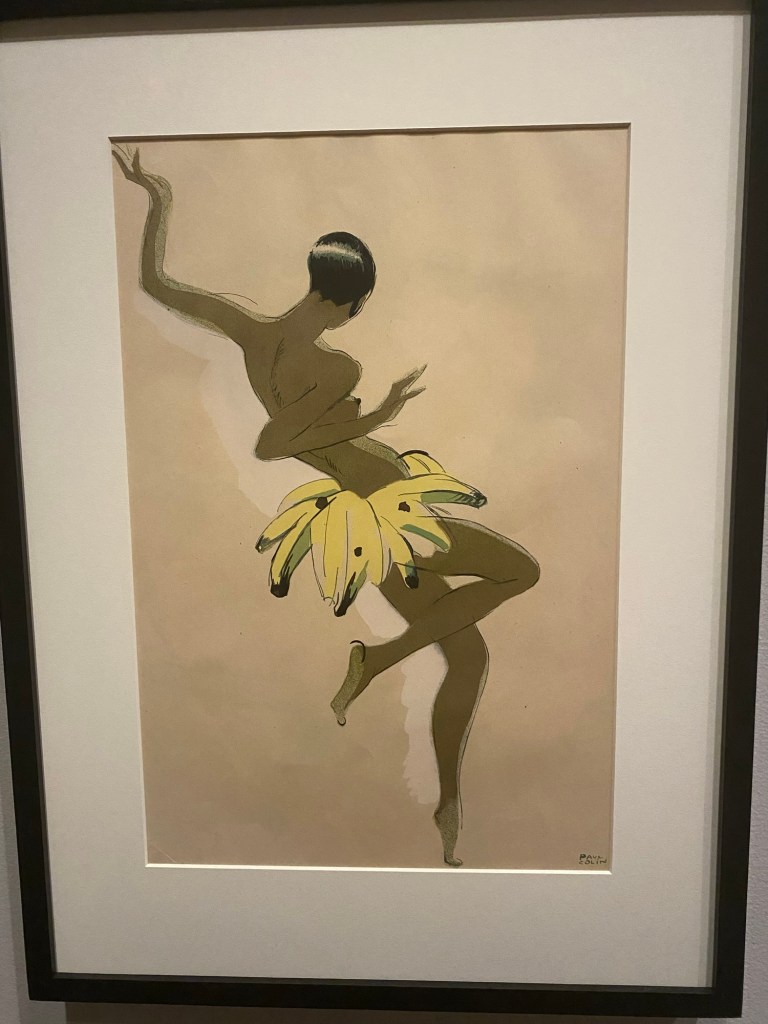

I focused on the Harlem Renaissance section of the exhibition, since this period fascinates me and offers many relevant lessons for creatives in the current day. I was thrilled to see some of my favorite artists represented in the collection, including Lois Maillou Jones, Augusta Savage, and Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller. And, naturally, no exhibition about the Harlem Renaissance would be complete without a Josephine Baker feature.

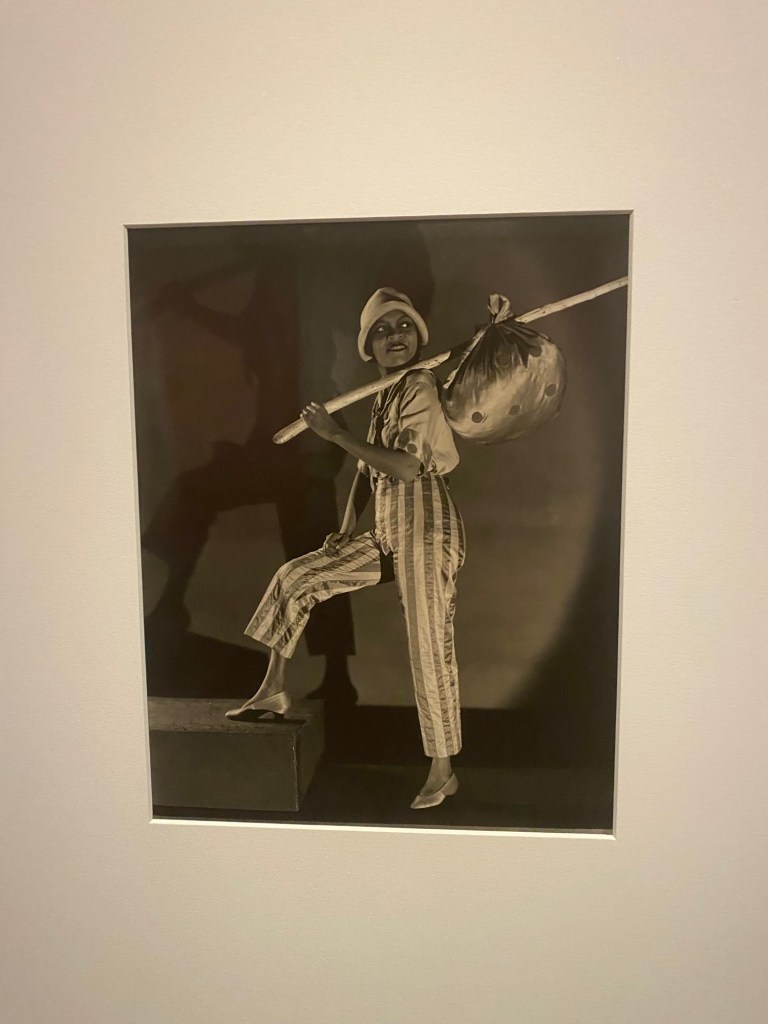

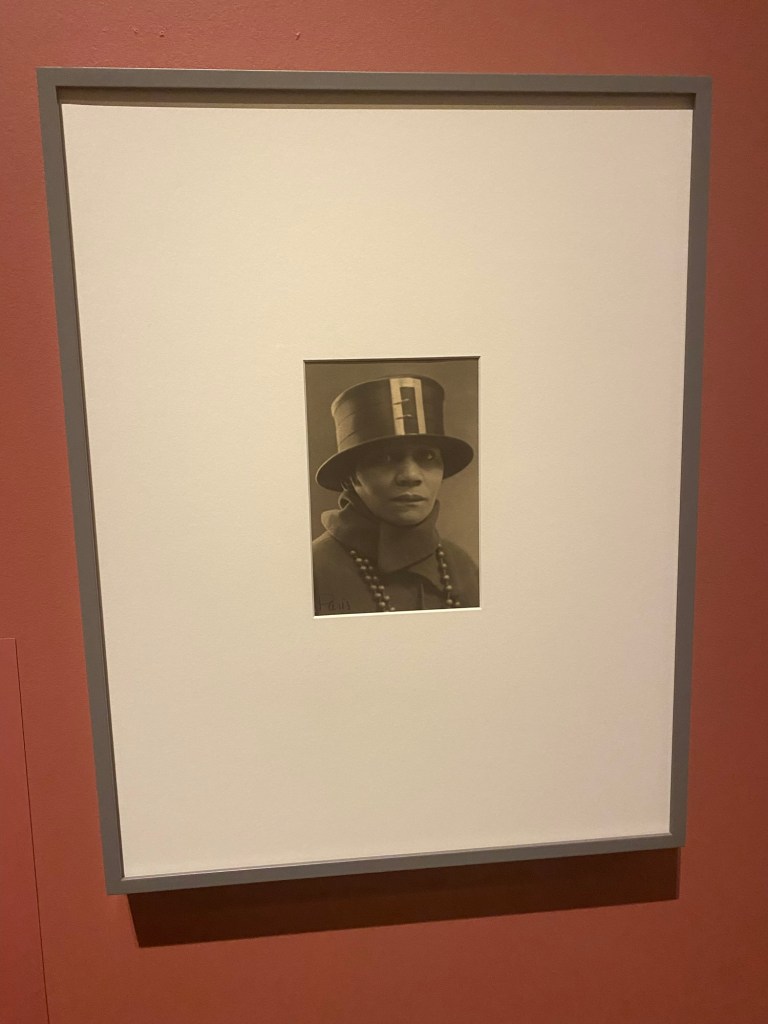

I was delighted to see other singers that are sometimes overlooked during the conversations around influential vocalists during this period. Florence Mills, Nora Holt, Adelaide Hall and Ethel Waters were also highlighted in this exhibition, which was a refreshing surprise.

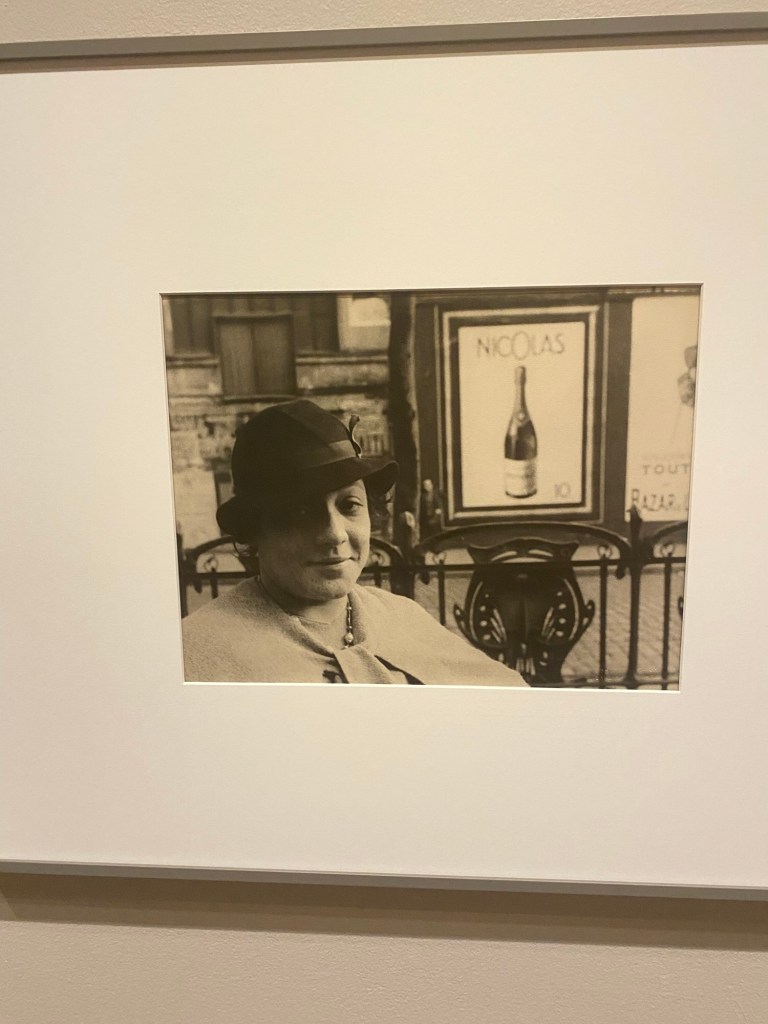

I was tickled to see a photograph of one of my favorite jazz-era entrepreneurs, Ada “Bricktop” Smith. Her Paris nightclub realized a level of success that Smith could have not even fathomed in America. I love that her entrepreneurial spirit led her to a foreign country, where she enjoyed a long and fruitful career.

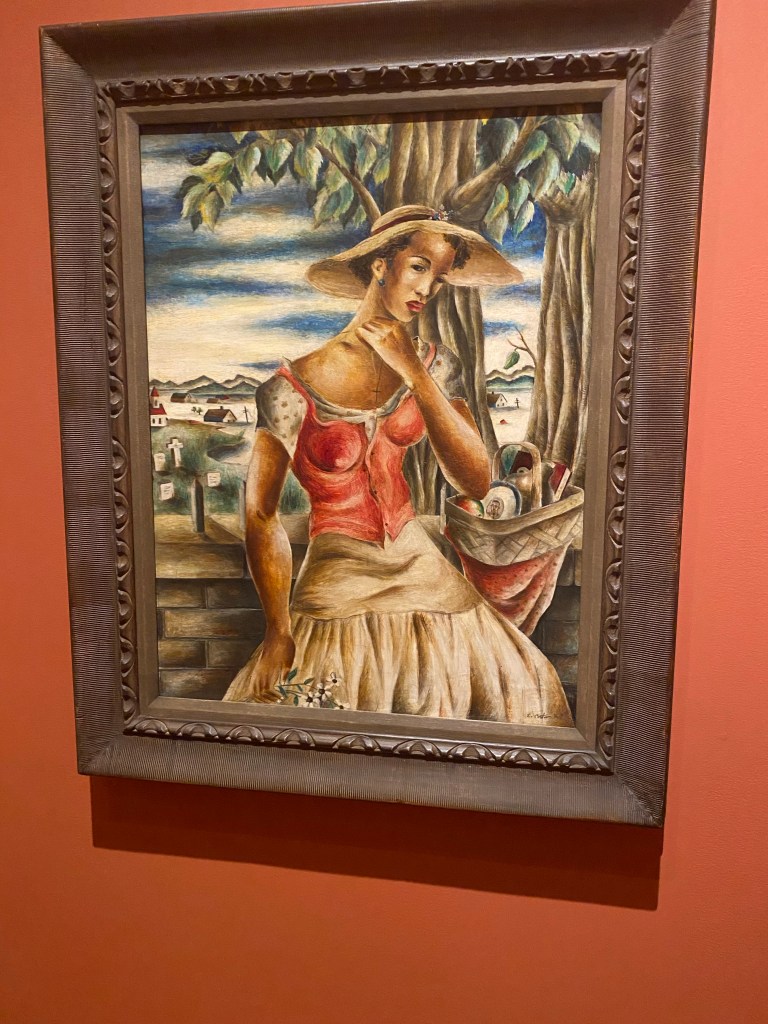

This collection also introduced me to Laura Wheeling Waring, an African American female portraitist that captured some of the most brilliant women of the time. I fell in love with her portrayal of Jessie Redmon Fauset, the poet and literary editor of The Crisis, a magazine that published the works of a number of Harlem Renaissance greats (such as Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Nella Larsen, and many others).

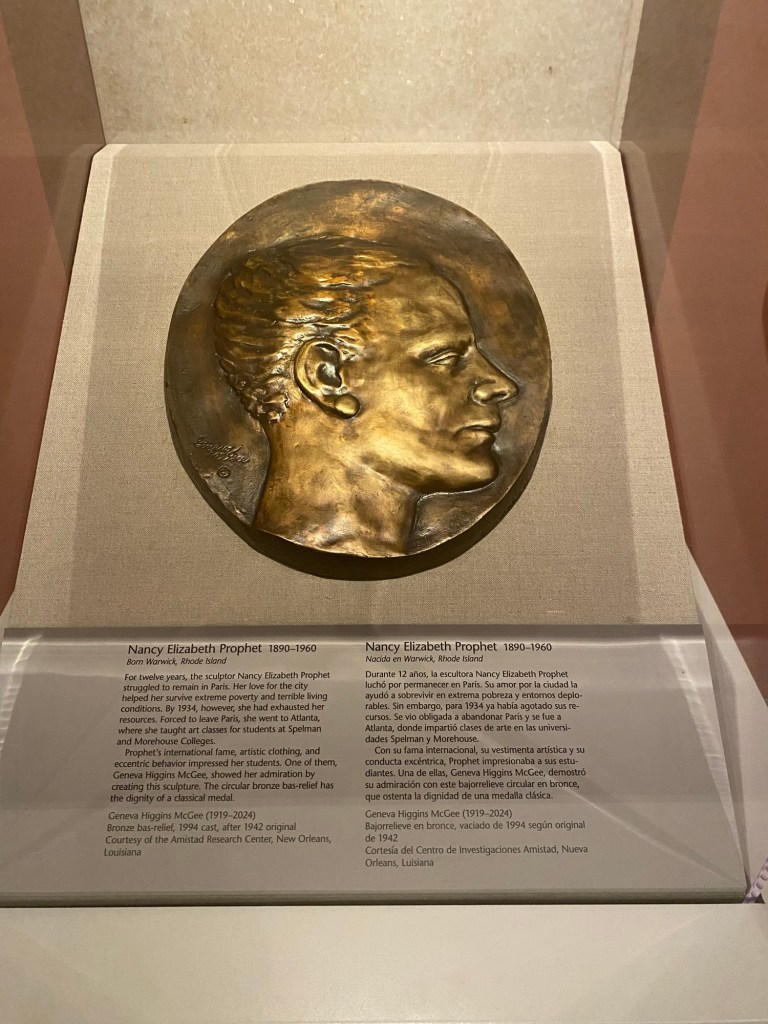

The exhibition also re-introduced me to Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, a sculptor that I’m excited to learn more about. I was captivated by her story, especially her diligence to her craft. She was so devoted to sculpting that she suffered through extreme poverty and physically demanding tasks (like carving stone and wood) in France, just to ensure that she could bring forth the art she desired to create. These hard times took a toll on her, but her efforts paid off, and she enjoyed success during her lifetime.

It warms my heart to know that, during a period of time where Black women in America were often pigeonholed into careers that were neither financially nor emotionally fulfilling, there were some brave and fortunate women that got to leave the States and experience peace and freedom in Paris. I am blessed to see portraits of these women, and even artwork that they created, during this exciting time in history.

The exhibition runs until February 23, 2025. I hope you all get a chance to check it out!